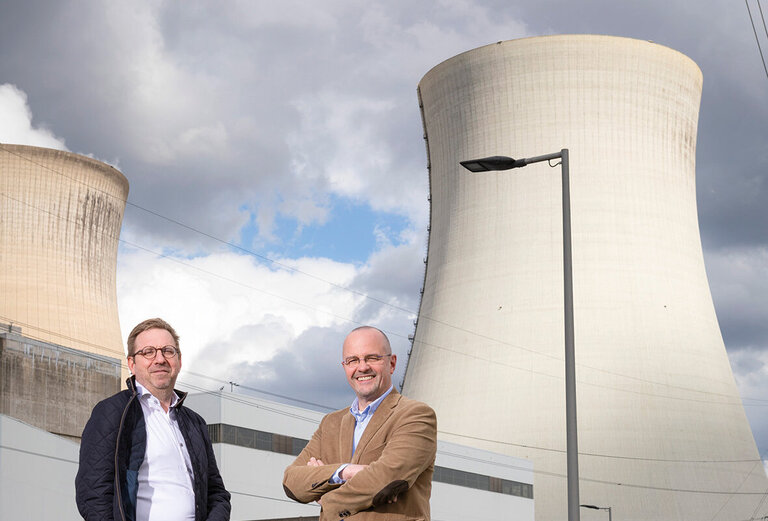

Peter Moens and Raf Verheyden (ENGIE Electrabel) on the decommissioning of Doel Nuclear Power Plant: 'An immense task in which safety is paramount'

Belgium is phasing out nuclear power. Last September, Doel 3 became the first nuclear power plant in Belgium to be disconnected from the grid, followed by Tihange 2 at the end of January this year. The shutdown simultaneously marks the beginning of a decades-long decommissioning phase. During this phase, the plant is stopped piece by piece, decommissioned, nuclear active or contaminated material treated, the buildings demolished and all material recycled as much as possible.

The situation at the site itself is complex because three power plants are still in operation: Doel 1, 2 and 4. The twin plants 1 & 2 will close in 2025 according to legislation. For Doel 4, negotiations are ongoing with the Belgian government for a possible 10-year extension of operation beyond 2025. 'That may become an additional challenge, as a nuclear power plant must by law always comply with state-of-the-art technology. Keeping Doel 4 open will require huge investments. To give you an idea: the lifetime extension of Doel 1 & 2 by ten years cost 700 million euros,' says Peter Moens, director of Doel Nuclear Power Plant. 'In addition, the current transition from the operation phase to the decommissioning phase naturally also has consequences for the work, for our people and the contractors we have working here. It's not just about demolition work. For decommissioning you need all kinds of new expertise and also new installations.'

Three phases

Decommissioning Manager Raf Verheyden adds, "We do the decommissioning of the nuclear power plant in three phases. In the first phase - the 'final shutdown phase' - we stop the reactor and cool the fuel elements in our fuel docks for about three years. Then they can be stored safely in specially designed containers. We do this initially on site, in a building specially designed for this purpose. We do this in anticipation of a final disposal site that the National Institution for Radioactive Waste and Enriched Fissile Materials NIRAS will determine, build and operate.'

'We also clean the "primary circuit" of the nuclear power plant during that phase. Radioactive water flowed into that circuit, causing radioactive particles on the pipes. We loosen those particles and capture them in resins. For Doel 3, that cleaning was successfully completed in April. Eventually, we will dispose of all other radioactive material from the fuel docks and all circuits will finally go out of service. We will be about five years down the road and have eliminated most of the nuclear risk.'

'Then phase two, the actual decommissioning, can start. We will need about seven years to decommission the major components, our 'Big Four' so to speak: the internals of the reactor, the primary circuit, the reactor vessel itself and the concrete shell around it. After further decontamination and release of buildings, we can begin phase 3: the actual demolition of the nuclear power plant. After that, the soil will be remediated and the site can be given a new industrial use in the distant future.'

Recycle as much as possible

The above may sound fairly simple, but it will eventually take about 20 years. 'The first phase is mainly to remove the nuclear risk so that decommissioning can proceed safely,' Raf emphasizes. 'With the chemical decontamination in Doel 3, for example, we have already removed over 99% of the radioactivity from the primary circuit in the last month. But that's only the first step.’ 'A big challenge, of course, is also the processing of all the materials and waste. We want to reduce those as much as possible. For example, we compress most of the radioactive waste in drums to minimum volumes. This is done in cooperation with Belgoprocess, a subsidiary of ONDRAF/NIRAS. We then want to recycle the waste from the regular industrial demolition phase as much as possible.'

Care for the environment

Peter: 'We are carrying out this project with care for our surroundings, employees, contractors including Bilfinger, local residents, local industry, with whom we want to work closely, and other stakeholders. There really is an incredible amount involved in the decommissioning of a nuclear power plant.' We will not lack for challenges in the coming years.

More information at nuclear.engie-electrabel.be/en

MP Henri Bontenbal (CDA):

'If climate really matters to you, choose nuclear power'

While nuclear power plants are closing in Belgium, the Netherlands is going to build at least two new nuclear power plants. For quite some time, MP Henri Bontenbal (CDA) has been concerned with the future of the energy system. This interest arose while studying physics. 'I have always been concerned with making energy supplies more sustainable,' Henri says. 'Initially I was fairly neutral about nuclear energy, especially when energy from the sun and wind at sea took off. But the higher the share of energy from solar and wind, the more you have to start thinking about the future of the total energy system. It must be CO2-free, affordable and offer security of supply. Especially the latter aspect has been underexposed. The Netherlands is a country with a relatively large amount of heavy industry and is constantly engaged in a battle for space: agriculture, housing construction and the energy transition are competing for space. All this added up, including the system costs, leads me to the conclusion that nuclear energy must be part of the energy mix of the future.'

Small Modular Reactors

'In the fight against climate change, we should not hold dogmas against nuclear power,' Henri believes. 'I expect that in 2050 we can get about three-quarters of our energy needs from solar and wind, and nuclear energy accounts for a quarter. In the latest coalition agreement, it has been agreed that we will build two new nuclear power plants in the Netherlands. If all goes well, they will be ready in 2035 and will then each have a capacity of 1,000 to 1,650 megawatts. In addition, I want to do everything possible to build a number of SMRs of between 10 and 500 megawatts as soon as possible. These Small Modular Reactors are safe and you can easily fit them where you need them. Especially in the industrial clusters they are an ideal solution, because there is a large electricity demand there and you don't have to increase the capacity of the entire Dutch electricity grid. Chemelot, the Maasvlakte and Zeeland spring to mind. I would prefer that we build these SMRs as soon as possible. In terms of location, for example, the coal-fired power plants on the Maasvlakte that need to be shut down are good places for an SMR, because the electricity infrastructure is already there anyway.'

Greta Thunberg

The final obstacle against the use of nuclear power is not in the technology, but in political dogmatism, Henri believes. ‘But when even the Greens in Finland want to build new nuclear power plants and Greta Thunberg calls for keeping Germany's nuclear power plants open, even as a politician you have to think twice. The younger generation seems to take a slightly more pragmatic view; they just want us to solve the climate problem. And rightly so. I think: if you really care about the climate, choose nuclear energy as part of your energy system!’